By Susanne Berger

August 4th marks Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg’s 111th birthday.

In 1944, Wallenberg accepted a diplomatic appointment to Nazi occupied Hungary where he managed to protect the lives of thousands of Jews. What Wallenberg brought to Budapest was the idea of hope and possibility – that, against all odds, rescue was indeed attainable and that humanistic ideas could prevail. His unflinching activism has crucial relevance and implications for today.

Myth making is always a form of simplification. When it goes too far, the essence of any problem is lost.

The dangers of mythification

Historians and journalists view events through a variety of prisms, so it is important to understand the philosophical underpinnings of their respective analyses. The case of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg is no exception. The past three decades have seen increasing efforts to arrive at a deeper, more realistic interpretation of both his person and his humanitarian mission to Hungary at the end of World War II, to protect the last surviving Jewish community in Budapest.

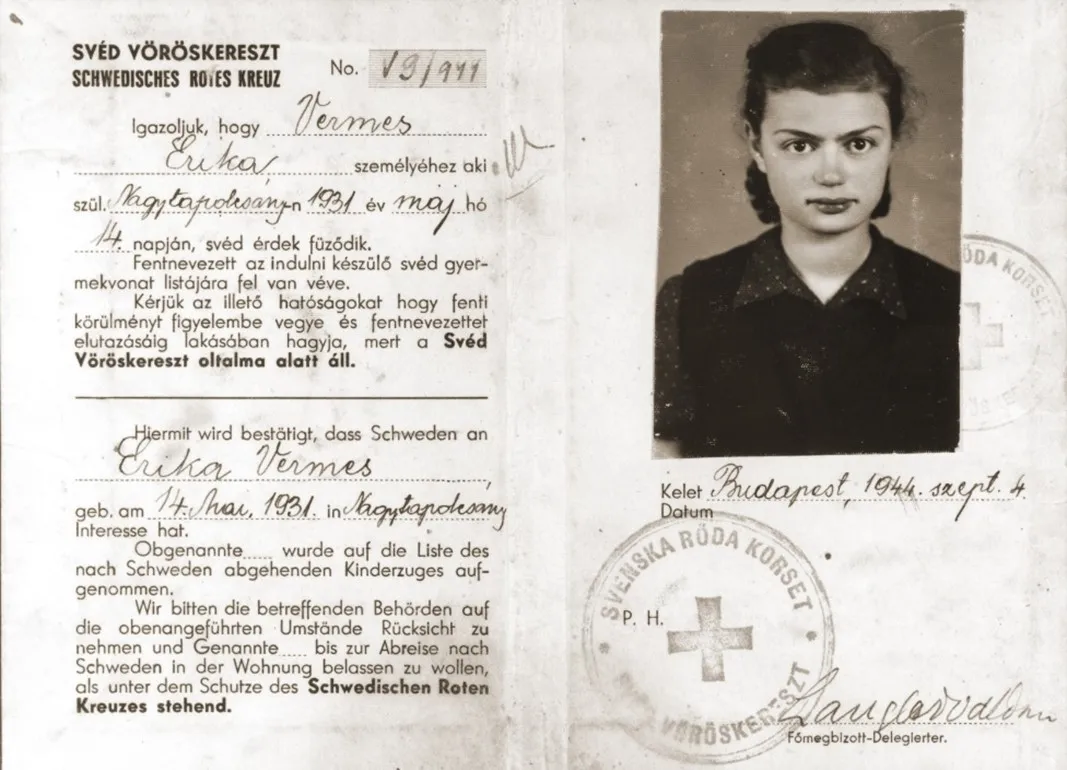

The historian Paul Levine (who passed away in 2019) argued that the post-war “myth making” around Raoul Wallenberg has prevented a realistic evaluation not only of his achievements but of the events in Hungary in general.[1] Specifically, Levine pointed out that far from acting alone, Wallenberg’s mission was made possible by a wide variety of factors – from the Swedish government’s decision to pursue a policy of ‘bureaucratic resistance’, formally backing the issuing of Swedish protective documents, the famous “Schutzpässe“ (protective passports) that were of doubtful legal validity; to the wide network of aides, fellow diplomats and members of the resistance who provided crucial manpower, expertise and local contacts.[2]

Levine undoubtedly has a point: In the end, “myth making” is always a form of simplification. When it goes too far, the essence of any problem is lost. Therefore, it is absolutely necessary to place Wallenberg into the broader historical context, because only then can the mechanisms of the Holocaust on all sides – perpetrators, victims, rescuers and bystanders – be fully analyzed and understood.